Kleros: Gaming in justice – Kleros response

The Kleros team’s response to the blog <Kleros: gaming in justice> By Abeer Sharma*

Editor’s note: On September 16, 2022, Cyberjustice Laboratory posted a blog about Kleros. And the Kleros team wanted to respond to some of the controversial points in that blog to promote a more in-depth discussion.

1. Introduction

This post is a response to a previous blog post by Jinzhe Tan titled, “Kleros: Gaming in Justice.” In his interesting post, Tan provides an overview of the decentralized justice mechanisms and expresses certain concerns and risks arising from the Kleros protocol. Since Tan has already provided an introduction to how Kleros works, we shall not be reintroducing the relevant concepts in this article. The focus of this post is to provide clarifications for some of Tan’s representations and responses to some of the criticisms that he has expressed.

2. On the difficulty of selecting Schelling points in some situations

In his post, Tan invokes a poll to illustrate an interesting concern about the difficulty of utilizing Schelling Point games for resolving questions which involve picking out a random number in a set, where all numbers in the set are equally non-distinct.

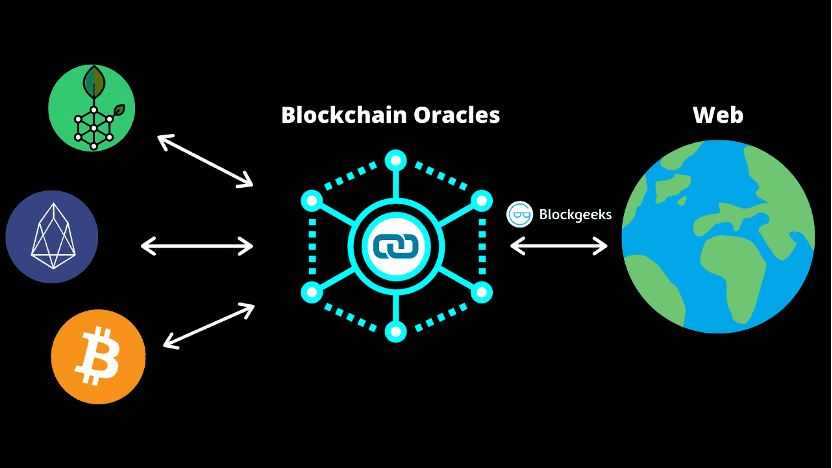

However, this may not be a problem for the questions resolved by Kleros. Here is where the distinction between “objective” oracles and “subjective” oracles becomes relevant. An oracle is any mechanism that feeds blockchain-based smart contracts with external information so that the smart contract can execute its functions.

Image source:https://blockgeeks.com/guides/blockchain-oracles/

An oracle can be objective, in the sense that the information being provided does not require the use of non-quantifiable human reasoning or value judgments, or it can be subjective, in the sense that the information is such that interpreting and comprehending it involves an element of human discretion. For instance, the question of how much a chicken weighs is an objective determination, whereas the question of whether the chicken should win a beauty pageant is a subjective determination.

While other tools in the ecosystem serve best as objective oracles[1] (E.g. Augur <https://augur.net/>), Kleros occupies the subjective oracle space, where questions resolved by jurors require them to appreciate evidence and utilize their subjective reasoning to make decisions in accordance with applicable norms; not much different from how judges or arbitrators make decisions.

It would thus be improbable that a Kleros jury would have to make a decision akin to an arbitrary selection of digits devoid of all normative context. In general, the nature of questions typically referred to Kleros for resolution should allow independently deliberating jurors to discern options that seem more “fair”.

Tan also quotes Thomas Schelling to highlight that, « the conspicuousness of the focal point depends on time, place and people themselves. It may not be a definite solution. »[2] This is most certainly true, and a significant amount of the Kleros Cooperative’s ongoing research work aims at exploring the amorphousness of focal points. However, this mere fact may not pose any unmanageable roadblocks to the adoption of Kleros in dispute resolution.

As of now, the categories of disputes that the Kleros protocol serves currently do not involve substantial invocations of jurors’ cultural backgrounds, but even if they did it may not necessarily be the case that normative judgments of people are completely fluid and detached from the commonality of the human condition. A body of research suggests the existence of hypernorms: “principles so fundamental that they constitute norms by which all others are to be judged.”[3][4] Proponents of this idea state that there are certain moral principles reflected at the convergence of religious, philosophical, and cultural beliefs such that they can be considered fundamental and axiomatic.[5] One such example of hypernorms would be the condemnation of bribery of public officials by contractors.[6] If this hypothesis is accepted, it would suggest that, at least in cases involving fundamental principles, no amount of jury diversity or spatio-temporal differences would pose difficulties in arriving at acceptable focal points.

Secondly, it is understood that, in some instances, disputing parties or other stakeholders may prefer the dispute to be referred to a qualified group of jurors for various reasons. These qualifications may relate to professional background, location, criminal history, or other relevant criteria. The Kleros Cooperative is conducting significant research in areas of web3 development such as soulbound tokens[7] to facilitate the design of such mechanisms without compromising the integrity of the decentralized system.

3. On the “simplicity” of Schelling Points

Next, Tan suggests that “The Schelling point is likely to be the simplest answer to an issue rather than the most correct one.” While it is not entirely clear what Tan means when he contrasts the “simplest answer” from the “most correct” one,[8] he may be referring to one or both of the following related phenomena: a) The “social loafing effect”, which describes the “tendency for individuals to expend less effort when working collectively than when working individually”[9], and b) The “lowest common denominator” risk, where the focal point risks manifesting as a solution that will cater to the heuristics of the least sophisticated and most simple-minded members of the community.

The social loafing or freeloader effect is a phenomenon typically observed in traditional juries.[10] In fact, the incorporation of cryptoeconomic incentives and appeal mechanisms within the Kleros protocol makes it less likely that any individual juror will forego careful deliberation and indulge in “lazy voting” strategies, as the existence of staking and slashing mechanisms within the decentralised court design are likely to ensure that such a voting strategy will, on average, lose.[11]

With respect to the lowest common denominator, the idea that crowdsourced juries will necessarily lead to dumbed down results is typically an argument rooted in elitism, and is merely a repackaged variant of arguments employed to oppose democracy.[12] In fact, a trove of existing research on the “wisdom of crowds” indicates that the decisions of crowds are often more “accurate” than those of experts.[13] For instance, studies have demonstrated that crowdsourced deliberations have been successfully leveraged to make accurate decisions on a range of complex questions, including in pandemic management,[14] medical mysteries,[15] and solving criminal cold cases.[16]

4. On conditions for ensuring successful crowd-judging

Of course, the above does not imply that the decisions of crowds cannot be flawed. Research indicates that the superiority of crowdsourcing over expert judgments can only be consistently achieved if the following conditions are met:[17]

(i) Diversity of opinions within the crowd to ensure variance in approaches and private information.

(ii) Independent thinking, where people’s opinions aren’t determined by the people around them.

(iii) Decentralization which ensures that people can specialize and draw on individual knowledge while not being subject to the directions of an overarching authority.

(iv) An aggregation mechanism to convert the private judgments of individuals into a collective decision.

(v) That individual decision-makers in the group trust that the group will come to a fair decision.

The Kleros protocol design by default takes care of conditions (iii) and (iv). Condition (v) is also substantially achieved as most users would not stake as jurors if they did not have some degree of trust over the mechanism design. Fulfilling condition (i) is certainly a factor that demands attention, and the Kleros Cooperative is actively undertaking research into best ensuring diverse juries.[18]

It may seem at first glance that condition (ii) is fatal to the Kleros protocol design, as the Schelling Point predicates a juror’s judgments upon the collective decision of every other juror. However, this is not necessarily the case. Contrary to what Tan states in his post, Kleros courts[19] do, in fact, allow jurors to communicate with each other and argue their positions. Not only do the disputing parties submit evidence, but jurors can similarly submit their analyses on IPFS for the world to see.[20]

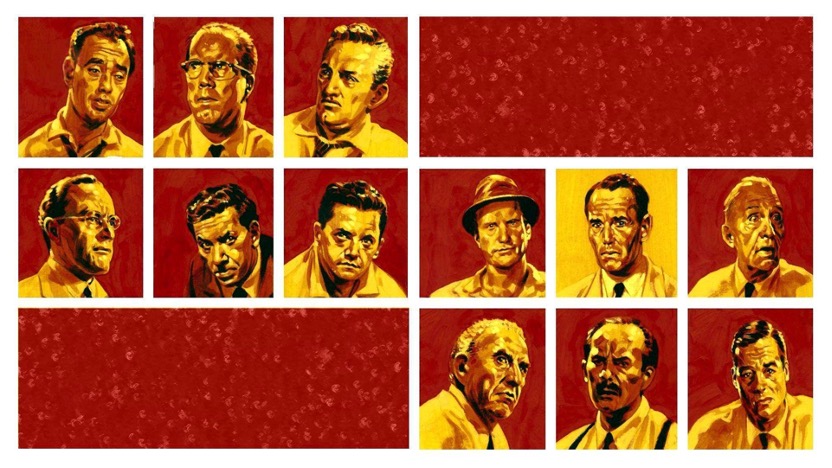

Jurors have also created chat groups on Telegram to discuss and debate disputes they have been drawn into.[21] These factors thereby facilitate the “12 Angry Men” scenario that Tan asserts would not happen in a Kleros case. Moreover, the current Kleros mechanism design allows individual jurors to appeal the outcome of a dispute in case they feel that the outcome is incorrect.[22]

Granted, it is possible that we may see cases where a juror in good faith believes that the correct decision is contrary to the collective decision of a robust crowd. We may also possibly witness potential edge cases where the core controversy is so fundamentally subjective that no amount of normative reasoning can provide a satisfactory conclusion. However, these same risks exist in every other known dispute resolution process. Every day we are likely to come across judicial judgments that we deem biased or incorrect. There is no way to ensure that Kleros keeps 100% of the people happy 100% of the time, but what we can be sure of is that the Kleros design minimizes the discretion and idiosyncrasies of any individual over the dispute resolution process. This can only be understood as an absolute win, considering that most of the disputes being targeted by Kleros are going unresolved by centralized dispute resolution forums.

5. On the flaws of jurors

Some of Tan’s objections concern potential weaknesses arising from the background or likely interactions of jurors. For instance, Tan suggests that it is possible for the jury to arrive at an “unreasonable” consensus due to the idiosyncratic composition of the jury pool or due to the emergence of “irrational rules” within the jury. This is most certainly a possibility, but a suitably-diverse juror pool would avoid any risks of any particular drawn jury being homogeneous to the point of irrationality. Well-crafted court policies[23] would also preempt the jury from relying on ad-hoc rules that are inappropriate for the dispute at hand. Tan also suggests that people are not only motivated by financial incentives, and that some jurors might have non-financial incentives to behave “unpredictably”. While this is no doubt true on an individual basis, one would expect that, on average, jurors that stake cryptoassets into Kleros courts do so with the expectation of earning rewards, thus maintaining the integrity of the mechanism design.

Tan also criticizes the fact that “in some complex cases, jurors without legal training may be influenced by superficial factors to reach an unjust conclusion.” However, this objection does not seem reasonable.

Firstly, due to the inherent nature of staking and slashing mechanisms, jurors are already subject to immense self-selection pressures that ensure they do not stake themselves into a court in which they do not have the required expertise.

Secondly, as stated above, it may in fact be possible to design courts that restrict participation only to qualified experts.

Thirdly, the author uncritically assumes that lay jurors are somehow more susceptible to superficial reasoning than lawyers. In fact, evidence suggests that trained judges are no less susceptible to an array of cognitive biases,[24] and they happen to be granted with far more discretion and immunity to implement these biases than a decentralized Kleros jury.

Kleros does not seek to replace the sovereign judicial system for all intents and purposes. It is, at its core, an alternative dispute mechanism that seeks to plug the justice gap which centralized processes have been unable to serve. There is thus no reason that it must parallel the composition of traditional systems to fulfill its purpose. For instance, maritime arbitration – a significant area of dispute resolution – is known for the large proportion of non-lawyer arbitrators that build successful careers.[25]

6. On attack vectors and design weaknesses

Tan’s post also touches upon the Kleros protocol’s defenses to certain attack vectors. Here it is important to note that the author is addressing outdated work. The white paper that he cites is from 2019, and has in the years since been replaced by the Kleros Yellow Paper.[26]

The author’s objection that the “Attack Resistance” section of White Paper only discusses two potential attack vectors over the protocol is resolved by the Yellow Paper,[27] which expands upon the list with new additions.[28]

On the topic of collusive attacks, the author is correct when he states that Schelling Points may theoretically be subject to collusive attacks, wherein a pool of jurors can enforce arbitrary decisions detached from the court policy or prevailing sense of fairness. However, this concern does not seem particularly likely in the case of the Kleros protocol.

Firstly, there is no existing way to identify each potential juror that may be drawn into the dispute over its life-cycle, and appellate mechanisms within the protocol design that continuously refer the the dispute to larger juries make juror collusion a particularly risky endeavor, even where the jurors are able to communicate their opinions about the case with one another. This is because all drawn jurors are ultimately rewarded or penalized based on the eventual outcome of the final appellate round. Even if in some way an attacker could identify and collude with all jurors in a specific round, there would be no way for said attacker to predict or control what jurors would be drawn in subsequent rounds once an appeal has been triggered. This uncertainty renders attempts to subvert the process through collusion a losing strategy. That being said, the author is absolutely correct when he states that collusive attacks are more likely in smaller juror pools, and much of the Kleros Cooperative’s efforts are thus directed towards increasing the active pool of jurors staking into Kleros courts.

7. On the tension between financial incentives and the motivation for justice

The final concerns aired by the author pertain to the incentive mechanism at the heart of the Kleros Protocol design. These objections are quite intuitive, as the protocol design grates against our traditional understanding of how juries should function. It is likely true, as Tan points out, that Kleros jurors may care only about money. In fact, the mechanism was designed to account for the assumption that every user may be a bad actor and yet be incentivized to cooperate towards a just result.

However, the author does not seem to explain how exactly a “just” verdict and economic incentives are mutually incompatible. It is not necessarily the author’s fault, however: unqualified assertions such as these tend to be prevalent across literature that seeks to attack cryptoeconomic design principles, most notably in the literature that the author has referred to in his blog post.[29]

Similarly, the author states that the process wherein a juror’s conclusion is derived from a prejudgment does not constitute a just result, but he provides no justification for such a claim. The entire basis for incorporating policies in Kleros courts[30] is to focus the jury’s deliberation on a set of norms and principles that may facilitate each individual juror’s prejudgment in a focused manner.

The only question that emerges here is: What exactly does the author view as a “just” result? This is not necessarily a rhetorical question. Firstly, the protocol promises a “fair” result more than a “just” result.[31] But semantic differences aside, the Kleros mechanism is designed essentially as a private dispute resolution mechanism. No person can be forced to participate in the process. The protocol’s legitimacy thus derives from whether it can keep delivering consistent, effective results for its users that they would otherwise be robbed of under the status quo. Even traditional ADR systems may not be best serving the needs of consumers well enough. For instance, in the UK, it has been reported that more than a quarter of surveyed consumers who participated in consumer disputes would not participate in consumer ADR again, compared to less than a fifth who felt the same way about consumer courts.[32]

The most common objections to ADR in consumer disputes include time, complexity, and costs concerns as well as concerns of bias.[33] Since processes like Kleros have been developed primarily to address the access to justice gap left by courts and ADR, the only convincing objection that opponents of decentralized justice can truly cite is if said processes were in some way consistently producing results that were patently more “unjust” than those produced by centralized processes.

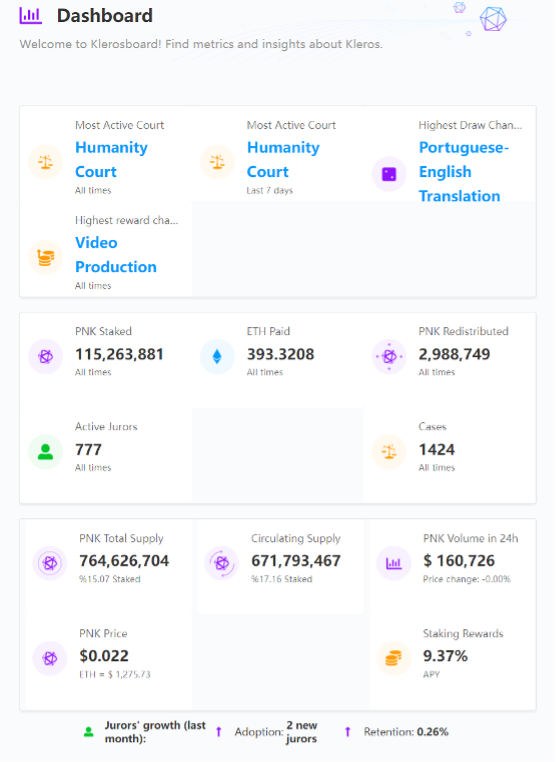

However, most critics have not so far managed to demonstrate the unjustness of Schelling Point-induced decisions via empirically sound evidence, preferring to engage instead in hand-wringing about the evils of money couched in ornate academic language. Ultimately, what we are left with is pages of what is essentially an appeal to personal incredulity.[34] At the time of writing, the Kleros protocol has resolved 1365 disputes by 779 jurors, and more are being added each day. It should thus not be difficult to identify potential design flaws in a more practical manner.[35]

Image source: https://klerosboard.com/#/1

Perhaps the author equates a just decision to one arrived at without economic incentive, purely based on a dispassionate assessment of evidence without a care for one’s own well-being?

If that is the case, then justice may not be found in this world, as evidence would suggest that judges are not much different from any other economic actors, motivated by both the pecuniary and non-pecuniary incentives of their jobs.[40] The same holds true for arbitrators, who are subject to a range of economically-motivated cognitive biases like the repeat player effect[41] and appointing party bias.[42] Unlike with decentralized processes, where the game theory mechanisms have been demonstrated to work against bribery attacks,[43] a simple google search will result in countless hits of the corruption of centralized decision makers.

Ultimately, while the Kleros protocol has not yet been demonstrated to be subject to any exclusive weaknesses that compromise the quality of its verdicts, it does benefit from one exclusive strength: the process is not subject to the discretionary authority of a single point of failure. The construction of sensible court policies ensures that the economic incentives are directed towards upholding agreed upon norms.

None of this should be interpreted to mean that processes like Kleros are perfect, or that they will retain an unblemished record. The possibility of a patently irrational decision will always be present. However, the critics of decentralized justice systems tend to exhibit the nirvana fallacy: they judge mechanisms like Kleros against an unattainable ideal while not subjecting all existing alternatives to the same rigorous scrutiny.

8. Conclusion

Tan concludes his observations by suggesting an experiment to compare the decisions delivered by Schelling Point-motivated juries against regular juries to ascertain whether there is any deviation. This is a good suggestion, even as a starting point for further, more sophisticated research on decentralized juries, and doubtless a study that should seriously be considered. It is intuitive enough that healthy debates about the challenges and opportunities of emerging technologies will allow us to carve out healthy niches for innovative mechanisms while respecting the interests of every potential stakeholder.

New technologies and processes

will understandably give cause for skepticism and concern. Such skepticism may

especially be warranted in the case of blockchain systems, an area of

development with a rabid subculture of ludicrous evangelists promising to

revolutionize every imaginable smidgen of human activity but instead producing

scams, market bubbles and failures. It would appear that innovations based on

crowdsourcing are a particular bait for skepticism, as our reliance on

technocratic institutions and possibly the bias of illusive superiority[60]

make most of us suspicious of the abilities of average people. However, such

biases may be unfounded. Crowdsourcing has already proven itself to be a

revolutionary process in the form of Wikipedia, which was similarly denounced

as an unreliable fad doomed to fail by its critics in its early days, only to

eventually become the internet’s favored resource for secondary research.

Kleros may yet facilitate the next paradigm shift for decentralized

crowdsourcing.

* Abeer Sharma is a PhD candidate at the University of Hong Kong and a member of Coopérative Kleros. Acknowledgments: The author thanks Federico Ast, William George, Yann Aouidef, and Jamilya Kamalova for their contributions to this article.

[1] E.g. Augur <https://augur.net/>

[2] Schelling, T. C. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[3] See, Donaldson, T. & Dunfee, T. W. (2002) Ties that bind in business ethics: Social contracts and why they matter. Journal of banking & finance. [Online] 26 (9), 1853–1865, 1858

[4] The idea of hypernorms also ties into the field of evolutionary ethics, which surmises that the moral sense common to humans has been instilled via natural selection pressures. See, Schroeder, D. Evolutionary Ethics, Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. Available at: https://iep.utm.edu/evol-eth/ (Accessed: November 24, 2022).

[5] See generally, Donaldson, T. & Dunfee, T. W. (1999) Ties that bind : a social contracts approach to business ethics. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

[6] Hartman, E. M. (2009) Principles and Hypernorms. Journal of business ethics. [Online] 88 (Suppl 4), 707–716.

[7] Weyl, E.G., Ohlhaver, P. and Buterin, V., 2022. Decentralized Society: Finding Web3’s Soul. Available at SSRN 4105763.

[8] For instance, according to Occam’s Razor: the simplest explanation is usually the correct one. See, Gibbs, P. and Hiroshi, S., 1997. What is Occam’s razor? <https://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/General/occam.html>

[9] Karau, S.J. and Williams, K.D., 1993. Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of personality and social psychology, 65(4), p.681.

[10] Najdowski, C.J., 2010. Jurors and social loafing: Factors that reduce participation during jury deliberations.

[11] George, W., 2018. Doges on Trial Part 3 – Cryptoeconomics Finale Edition <https://blog.kleros.io/doges-on-trial-pt3-cryptoeconomics/>

[12] See e.g. generally, Femia, J. V. (2001) Against the masses: varieties of anti-democratic thought since the French Revolution. Oxford ;: Oxford University Press.

[13] See generally, Surowiecki, J., 2005. The wisdom of crowds. Anchor.

[14] Turiel, J., Fernandez-Reyes, D. and Aste, T., 2021. Wisdom of crowds detects COVID-19 severity ahead of officially available data. Scientific Reports, 11(1), pp.1-9.

[15] Gardiner, A. (2019) For ‘diagnosis’ show, dr. Lisa Sanders lets Times readers around the world join in the detective work, The New York Times. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/16/reader-center/diagnosis-tv-netflix.html (Accessed: November 8, 2022).

[16] Jitchotvisut, J. (2018) 8 times crimes were solved by the internet, Insider. Insider. Available at: https://www.insider.com/crimes-solved-by-people-online-2018-5 (Accessed: November 8, 2022).

[17] Surowiecki, (fn 13)

[18] George, W. (2022) Economic Incentives and Souls in Schelling-point Based Oracles, YouTube. Ethereum Foundation. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKpVzdUvXE0 (Accessed: November 8, 2022).; Hong, L. and Page, S.E., 2004. Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(46), pp.16385-16389.

[19] “Courts” or “subcourts” are terms used to denote a collection of Kleros smart contracts and DApps that function as a meeting point for jurors and parties, where disputes of a specified shared classification may be grouped together.

[20] See e.g. Kleros case # 1170 <https://court.kleros.io/cases/1170>

[21] See, “Kleros heated juror chit-chat group” Telegram <https://web.telegram.org/?legacy=1#/im?p=@klerosjuror>

[22] See, https://etherscan.io/address/0xba0304273a54dfec1fc7f4bccbf4b15519aecf15#code

[23] Kleros court policies function as the “law” for any dispute that falls under the ambit of the specified court.

[24] Peer, E. and Gamliel, E., 2013. Heuristics and biases in judicial decisions. Ct. Rev., 49, p.114.

[25] See, Lambrou, G.L. (2021) International Maritime Arbitration: How to get those skills ship-shape, CIArb. Available at: https://www.ciarb.org/resources/features/international-maritime-arbitration-how-to-get-those-skills-ship-shape/ (Accessed: November 8, 2022).

[26] Lesaege, C., George, W., and Ast, F. (2021). Long Paper v2.0.2 <https://kleros.io/yellowpaper.pdf> (Accessed: November 8, 2022).

[27] Ibid, p. 45-49.

[28] However it is still important to note that the White Paper discusses types of attacks in other sections of the paper, such as sybil attacks.

[29] E.g., Matthew Dylag & Harrison Smith (2021) From cryptocurrencies to cryptocourts: blockchain and the financialization of dispute resolution platforms, Information, Communication & Society, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.1942958

[30] These policies are voted in by the DAO of PNK token-holders.

[31] It has been stated that this distinction may be important in certain contexts. See e.g., University, S.C. Justice and fairness, Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. Available at: https://www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/ethical-decision-making/justice-and-fairness/

(Accessed: November 23, 2022).

[32] RESOLVING CONSUMER DISPUTES – Alternative Dispute Resolution and the Court System – Final Report (2018). BEIS. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/698442/Final_report_-_Resolving_consumer_disputes.pdf (Accessed: November 19, 2022). Pg 17

[33] Ibid 20-23

[34] The paper written by Dylag & Harrison (fn 29) is a prime example of such an instance.

[35] See, Klerosboard. Available at: https://klerosboard.com/#/1

[36] Ibid 20-23

[37] The paper written by Dylag & Harrison (fn 29) is a prime example of such an instance.

[38] See, Klerosboard. Available at: https://klerosboard.com/#/1

[39] Epstein, L., Landes, W.M. and Posner, R.A., 2013. The behavior of federal judges: a theoretical and empirical study of rational choice. Harvard University Press. Vancouver

[40] Epstein, L., Landes, W.M. and Posner, R.A., 2013. The behavior of federal judges: a theoretical and empirical study of rational choice. Harvard University Press. Vancouver

[41]Colvin, A.J., 2011. An empirical study of employment arbitration: Case outcomes and processes. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 8(1), pp.1-23. Vancouver

[42] Paulsson, J., 2010. Moral hazard in international dispute resolution. ICSID review, 25(2), pp.339-355. Vancouver

[43] William George, Doges on Trial Observations Part 2 – Deep Dive Edition Kleros (2018), https://blog.kleros.io/cryptoeconomic-deep-dive-doges-on-trial/

[44] Ibid 20-23

[45] The paper written by Dylag & Harrison (fn 29) is a prime example of such an instance.

[46] See, Klerosboard. Available at: https://klerosboard.com/#/1

[47] Epstein, L., Landes, W.M. and Posner, R.A., 2013. The behavior of federal judges: a theoretical and empirical study of rational choice. Harvard University Press. Vancouver

[48] Epstein, L., Landes, W.M. and Posner, R.A., 2013. The behavior of federal judges: a theoretical and empirical study of rational choice. Harvard University Press. Vancouver

[49]Colvin, A.J., 2011. An empirical study of employment arbitration: Case outcomes and processes. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 8(1), pp.1-23. Vancouver

[50] Paulsson, J., 2010. Moral hazard in international dispute resolution. ICSID review, 25(2), pp.339-355. Vancouver

[51] William George, Doges on Trial Observations Part 2 – Deep Dive Edition Kleros (2018), https://blog.kleros.io/cryptoeconomic-deep-dive-doges-on-trial/

[52] Ibid 20-23

[53] The paper written by Dylag & Harrison (fn 29) is a prime example of such an instance.

[54] See, Klerosboard. Available at: https://klerosboard.com/#/1

[55] Epstein, L., Landes, W.M. and Posner, R.A., 2013. The behavior of federal judges: a theoretical and empirical study of rational choice. Harvard University Press. Vancouver

[56] Epstein, L., Landes, W.M. and Posner, R.A., 2013. The behavior of federal judges: a theoretical and empirical study of rational choice. Harvard University Press. Vancouver

[57]Colvin, A.J., 2011. An empirical study of employment arbitration: Case outcomes and processes. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 8(1), pp.1-23. Vancouver

[58] Paulsson, J., 2010. Moral hazard in international dispute resolution. ICSID review, 25(2), pp.339-355. Vancouver

[59] William George, Doges on Trial Observations Part 2 – Deep Dive Edition Kleros (2018), https://blog.kleros.io/cryptoeconomic-deep-dive-doges-on-trial/

[60] Williams, E.F. and Gilovich, T., 2008. Do people really believe they are above average?. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(4), pp.1121-1128.

Ce contenu a été mis à jour le 9 mars 2023 à 15 h 11 min.