Kleros: gaming in justice

Written by Jinzhe Tan, Research Assistant at the Cyberjustice Laboratory and PhD Student at Université de Montréal

1. Introduction

In our last blog, we explored the future of ODR technology together. In it, we briefly mentioned several platforms that are revolutionizing dispute resolution mechanisms by applying blockchain technology and smart contracts, and named the new mechanisms decentralized justice. Today we will take a closer look at an important example of decentralized justice: Kleros.

As an innovation of the traditional ODR mechanism, Kleros mainly tries to solve two problems faced by the traditional ODR mechanism:

a. The problem of the last mile of smart contracts. There are several problems in the current execution of smart contracts. Although the smart contract itself can be executed automatically when pre-defined conditions are met, once a dispute occurs, numerous additional information is not stored on the blockchain, which leads to still having to resort to traditional dispute resolution mechanisms. Although ODR has been greatly improved in efficiency compared to courts and arbitration, there is still room for improvement.

b. Lack of incentives for participants and platform operators. One of the major challenges facing traditional ODR mechanisms is the inability to find a business model that provides sufficient incentives for disputants to choose the dispute resolution mechanism while also ensuring the profitability of the ODR platform operator.[1]

For problem a, Kleros wants to integrate blockchain technology as well as smart contract technology to build a dispute resolution mechanism that is automatically provided when a dispute arises in a smart contract and is automatically enforced after arbitration is completed. It is easy to see that Kleros provides a coherent experience that can improve the efficiency of dispute resolution.

To further increase its efficiency, it has also chosen to crowdsource jurors and does not substantially vet them. When a dispute arises, Kleros uses a randomized algorithm to assign the crowdfunded jurors to the dispute, and the jurors vote after analyzing the materials in the case.[2]

And Kleros has even bigger ambitions, claiming on its white paper that it “is a decision protocol for a multipurpose court system able to solve every kind of dispute.”[3]

For problem b, Kleros has introduced cryptocurrency into the dispute resolution mechanism. Rather than relying on the traditional moral sense of the jurors, Kleros uses game theory, which uses purely economic incentives to facilitate jurors to reach a just verdict. Kleros claims that they use “Schelling point” from game theory to support this mechanism, which we discuss further below.

The basic mechanism of the financial incentive system is that jurors are required to carefully review the materials submitted by the disputing parties and make their own judgments without being able to communicate with other jurors, and if a juror makes a judgment that is consistent with the majority judgment, then that juror will be rewarded with a certain amount of cryptocurrency and penalized for the opposite.

This innovative approach is bound to attract much controversy and criticism, and a test of its robustness is the best way to respond.

2. Moral principles and game theory

2.1 What is the Schelling point in game theory?

Schelling’s point describes a situation where everyone tends to choose an identical outcome in the absence of mutual communication between players.

Imagine a group of students from Université de Montréal deciding to meet somewhere. Even when they are not interacting with each other, they usually choose to meet in Local Local, the largest cafeteria in the university. There is nothing special about this cafeteria compared to the other places, but it is a regular choice because it is simpler and everyone knows where it is located.

There are also relevant examples in road traffic, such as whether a car should go along the left side of the road or should go along the right side of the road. No matter what the outcome of the choice is, efficiency can be promoted only if everyone chooses the same side, so the law will provide a Schelling point that allows everyone to choose the same side without communicating with each other.

To give you a better idea of the concept of Schelling points and to perceive the problems that can result from their use in the field of dispute resolution, we invite you to play two simple games, in which you win the game as long as the number you choose is the most chosen one.

Feel confused and hard to choose? Let’s try playing another game.

You may observe that because the second game option (a) is significantly different from the other options, it greatly increases the probability that players will choose option (a). Because players anticipate that other players will have a high probability of choosing (a), option (a) becomes a Schelling point in this game. All players tend to choose the same option without communicating with each other.

But the Schelling point is not a definite and constant point. Schelling states that « (p)eople can often concert their intentions or expectations with others if each knows that the other is trying to do the same » in a cooperative situation (at page 57), so their action would converge on a focal point which has some kind of prominence compared with the environment. However, the conspicuousness of the focal point depends on time, place and people themselves. It may not be a definite solution.[4

2.2 The design of Kleros and its problems

After we have roughly understood Schelling points, let’s go back to Kleros. Kleros wants to urge jurors to carefully review the materials in order to come up with the most just result with a reward and punishment model, so that with the efforts of all jurors, each juror will lean towards a just result based on the case materials, and jurors who end up voting the same as the majority will be rewarded, while jurors whose votes do not match those of the majority are punished.

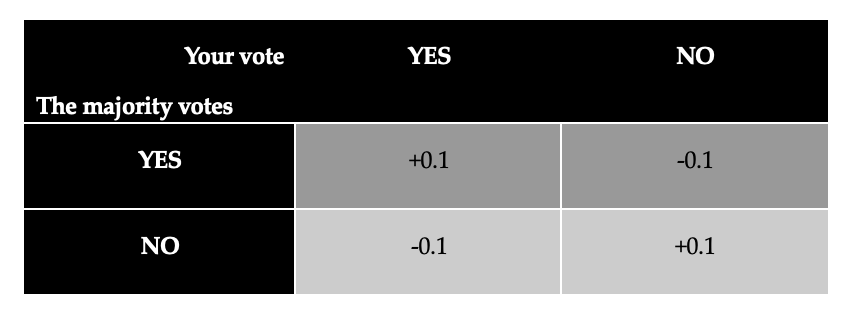

The following table shows the game mechanics used by Kleros:

Source: https://kleros.io/static/whitepaper_en-8bd3a0480b45c39899787e17049ded26.pdf

One of Kleors’ important assumptions about this game mechanics is that a juror’s verdict based on the Schelling point is equal to a just verdict.

In practice, however, there are many possibilities for the two to be unequal:

a. The Schelling point is likely to be the simplest answer to an issue rather than the most correct one. In some complex cases, jurors without legal training may be influenced by superficial factors to reach an unjust conclusion, and the lack of opportunity for jurors to interact with others further reduces the likelihood that jurors will correct their own wrong judgments.

b. In Kleros’ system, arriving at a just verdict is the expectation of the platform, but not the expectation of the jurors, and if the jurors’ goal is to gain an economic incentive, they will do everything they can to try expecting “what people expect that others expect them to be expected[5]”. It is about one juror’s prejudgment of what other jurors might conclude, and it does not mean that this is a just result.

c. Schelling points may be subject to collusive attacks. For example, a group of jurors agrees on certain rules and vote according to these rules regardless of what happens to ensure that everyone gets the benefit with high efficiency, a situation that is more likely to be implemented when the total juror pool of the Kleros platform is still relatively small.

d. Schelling points may be affected by some unreasonable consensus. This situation may still occur even when the platform is so large that it is difficult to be attacked by collusion. For example, at middle school or high school, there is always a strange rule circulating among students: when faced with a multiple choice question that they cannot solve, they should choose C. This rumor has led to a dramatic increase in the number of people picking C when presented with difficult questions. If such an irrational rule (which is easily generated and popularized by the economic incentive and the pressure of a complex case) circulates among the jurors in Kleros, it would further strengthen the credibility of the rumor, since in that system everyone is rewarded if they all choose according to an irrational rule.

e. Jurors’ unpredictable motivations. In the second mini-game we played above, we can see that even though there is an obvious Schelling point (a), and choosing (a) wins the game, there are still people who choose other options. It is possible that some of the players did not observe the presence of the Schelling point, but it is also possible that others were not motivated to win the game, but enjoyed choosing a different option, they were curious to experience what would happen if they chose a different outcome, etc. Kleros also cannot guarantee that running a dispute resolution platform using economic incentives will guarantee that everyone will expect to receive an economic incentive.

2.3 Kleros’ self-defense

There’s nothing wrong with sticking to Schelling points for things like choosing a meeting place, because no matter where you choose, you only need to end up at the same place. But in dispute resolution, if people choose a certain result because of the influence of Schelling point, it may lead to the deviation of the result that people choose from the ethical result.

And because there is no communication between jurors in the Kleros platform, it is also difficult to have a situation like the movie “12 Angry Men”, where people find out the omission of their original judgment through communication and thus correct their opinions.

The developers of Kleros also understand that making changes to the underlying mechanism in dispute resolution can have an impact on shaking up the fairness of the system, so they have discussed this issue in their blog.[6] They use the competition between Wikipedia and traditional encyclopedias to illustrate that a decentralized structure has the potential to produce results that are more accurate and trustworthy. But we should still be aware that in the legal field, or dispute resolution, people demand a high level of accuracy in results, and even today, Wikipedia is not recommended as a reliable source of legal literature.

For robustness tests, Kleros specifically lists a section of Attack Resistance in its white paper, but it only responds to two cases of collusive attacks[7].

a. Buying half of the tokens. Kleros’ response to this is that it is very difficult to buy half of the tokens, and the marginal cost will grow over time. This does not seem to be an adequate response.

b. Bribe resistance. The developers of Kleros believe that designing an appeal mechanism would substantially limit the success rate of bribery.

The developers of Kleros have not provided a reasonable response to other situations that potentially affect the justice of the Kleros.

William George, the blockchain and cryptoeconomics researcher for Kleros, writes a series of insightful blogs about Kleros, in which he writes about Kleros “keeping people honest on the blockchain through game theory”, in some cases, game theory Participants in the system will make ethical choices for reasons such as economic incentives, but this is essentially different from “keeping people honest”. Because in other cases, when incentives and moral standards are misaligned, players in a game theory system will inevitably choose immoral outcomes based on economic incentives and other reasons. Kleros avoided answering this question, saying that the world does not have a completely fair trial system, which is of course true, but we cannot allow potentially great dangers to persist in the system.

The traditional moral based judge trial has many flaws though, such as judges can be influenced by extraneous factors[8]. Even in a pure comparison of moral principles and economic incentives, it is difficult to argue that economic incentives have a greater binding effect on people’s behavior. Empirical research done by Zev Eigen, a professor at Northwestern University, shows that people are more likely to choose to default when they face an economic default and less likely to choose to default when they face a moral default. That is to say, the change in the underlying mechanism of dispute resolution made by Kleros may be to replace a more reliable mechanism with a more unreliable mechanism.

At the same time, Kleros is unable to ensure that the person in question conducts a random vote. “Kleros does not have a specific way to make sure that jurors reviewed the evidence. The way to make sure that jurors act honestly is through the creation of the right economic incentives. Jurors who vote randomly without reviewing the evidence are more likely to vote incoherently with the majority and lose the token they staked to be drawn. Hence, they lose money on average. Over time, this would make dishonest jurors leave the court[9].”

Kleros also could not guarantee that participants would use financial incentives as their primary motivation. The developers of Kleros have also reflected on this issue in their blog, but only to say that with good system design, people will act in the direction of maximum economic benefit.

As a future scenario, if we want to understand more precisely whether the Kleros mechanism will go wrong in practice due to the presence of improper Schelling points, we can conduct an experiment.

Find a random group of people and divide them into two groups, A and B. Give group A a case with a clear Schelling point, and if they vote according to this Schelling point, they will be rewarded with an unjust or partially unjust result, and give group B a case with just the Schelling point removed, keeping everything else the same. It will then be observed to see if Team A and Team B will make different decisions under the influence of the Schelling point.

In general, there is still a huge obstacle in front of Kleros, which is a problem that must be faced when innovating the underlying dispute resolution mechanism. Even if Kleros cannot prove that economic incentives are better than moral principles, at least Kleros needs to prove that the use of economic incentives can increase efficiency without causing large-scale unjust results, so that the platform can at least use the appeal mechanism to correct the unjust results.

3. Conclusion

Decentralization is sometimes good for equality and justice, but it is not always good to introduce decentralization into every field. In the judicial field, the morality of jurors has been used as the core of judicial decisions, which may be a path dependence in the history of human judicial decision development, and it is also possible that morality has an irreplaceable role.

Using game theory to replace the moral sense of jurors is a disruptive innovation in the field of dispute resolution, and whether successful or not, Kleros is a great practice. Such innovation will bring some problems while bringing excellent new features. Although we have raised some doubts about this, it does not prevent us from thinking that kleros has a promising future. We can expect the designers of kleros to find a more complete solution to these special situations. After the above problems are solved, we believe that kleros can be better developed.

For more information:

Matthew Dylag & Harrison Smith (2021) From cryptocurrencies to cryptocourts: blockchain and the financialization of dispute resolution platforms, Information, Communication & Society, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.1942958

[1] Mohamed S Abdel Wahab, M Ethan Katsh, & Daniel Rainey, Online dispute resolution: theory and practice: a treatise on technology and dispute resolution, Second Edition (Eleven International Publishing, 2021) at 591.

[2] Darcy W E Allen, Aaron M Lane & Marta Poblet, “The Governance of Blockchain Dispute Resolution” (2019) 25:1 Harv Negot L Rev 75–102 at 93.

[3] Lesaege, C., & Ast, F. (2019). Short Paper v1. 0.7 Clément Lesaege, Federico Ast, and William George September 2019.

[4] Schelling, T. C. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[5] Ibid.

[6] https://blog.kleros.io/is-kleros-a-fair-dispute-resolution-system/

[7] Lesaege, C., & Ast, F. (2019). Short Paper v1. 0.7 Clément Lesaege, Federico Ast, and William George September 2019.

[8] John Zhuang Liu & Xueyao Li, “Legal Techniques for Rationalizing Biased Judicial Decisions: Evidence from Experiments with Real Judges” (2019) 16:3 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 630–670.

[9] https://kleros.gitbook.io/docs/kleros-faq

Ce contenu a été mis à jour le 21 février 2023 à 9 h 28 min.